In one sentence: Nosferatu follows Thomas Hutter’s journey from Wisborg to Transylvania to meet Count Orlok, whose later arrival in Wisborg unleashes death on the town.

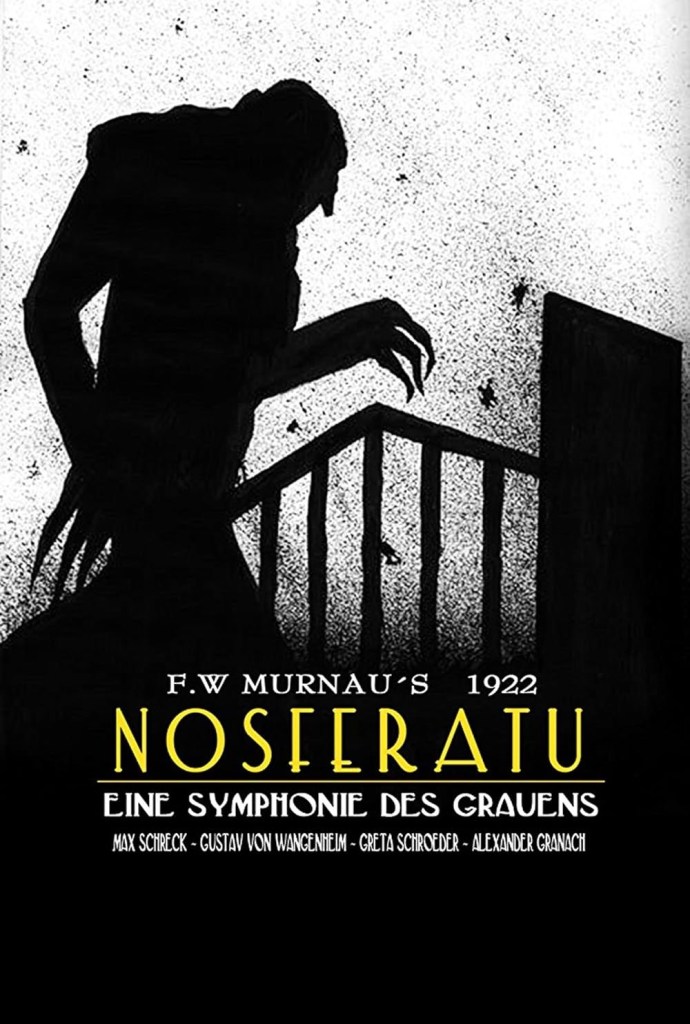

Vampire films remain endlessly popular, with new interpretations emerging every year, some even earning critical acclaim, such as the recent Sinners. However, long before glossy romances or glittering immortals, there was one film that shaped the cinematic vampire more than any other. Though its status as the first vampire film is debated, with contenders like Le Manoir du Diable (1896) and The Vampyre (1913), F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) remains arguably the most influential and, in many ways, the most unsettling.

The film follows Thomas Hutter, who travels from Wisborg to Transylvania at the request of his employer to sell a property to the mysterious Count Orlok. Along the way, he encounters locals terrified of the Count and soon learns why. Orlok reveals himself as a bloodthirsty creature, traumatising Hutter. Meanwhile, Hutter’s wife Ellen suffers from dread back home, and Orlok travels by sea toward Wisborg, bringing plague, death and fear with him.

The plot mirrors Bram Stoker’s Dracula so closely that Stoker’s widow attempted to have every print of the film destroyed for copyright infringement. The fact that Nosferatu survived at all feels significant. Had she succeeded, the trajectory of vampire cinema, or even horror, might look entirely different.

Horror often reflects the anxieties of its era. Today, films grapple with AI, pandemics, and technological dread. In 1920s Germany, trauma took a different shape. The First World War had ended, leaving devastation, grief, and a generation psychologically scarred. Art from this period, from Otto Dix’s war etchings to Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, reveals a culture processing unbearable loss. Nosferatu emerged directly from this moment as part of German Expressionism, known for stark shadows and distorted imagery. Yet it also broke new ground by using real locations rather than studio sets, negative film, blue tints to represent nighttime and simple but astonishing practical effects.

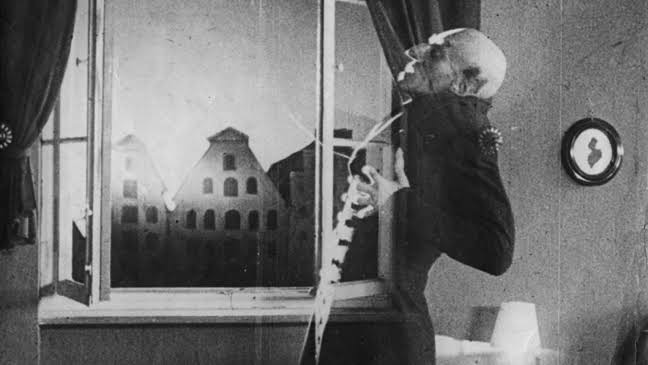

Producer Albin Grau famously described war as a “cosmic vampire” and the parallels are striking. The name Orlok evokes the Dutch oorlog, meaning war. Orlok moves through fog like poison gas. He sleeps in a coffin filled with soil and rats, reminiscent of the trenches. Hutter returns home haunted and traumatised. He is a shell of the cheerful man who first set out. The metaphor is a representation of Germany’s lost generation. We also see Ellen struggling at home, representing the fears of the home front.

There is also scholarly discussion around antisemitic imagery, particularly as the Nazi Party was gaining influence. Orlok’s, associations with plague and use of Hebrew inscriptions reflect anxieties and prejudices that would soon shape history in devastating ways.

Max Schreck’s performance as Orlok remains extraordinary. He appears on screen for only nine minutes and reportedly blinks once, yet his presence dominates the film. His movements are slow and deliberate, his silhouette unforgettable. His very name Schreck (not a stage name) meaning ‘fright’ in German added to speculation he was a real vampire, a myth later explored in Shadow of the Vampire (2000).

One of Nosferatu’s most lasting influences is the idea that sunlight kills vampires. In Dracula, sunlight merely weakens. In Nosferatu, it destroys and this single alteration has echoed through a century of vampire storytelling.

Nosferatu has inspired several remakes, including Werner Herzog’s 1979 version and the recent 2024 remake. As we have become more desensitised to horror, modern audiences may longer find the original so frightening, but its imagery, atmosphere and symbolism remain deeply eerie.

It is still, in many ways, the definitive vampire film.

★★★★½ (4.5/5)